The End Before the Beginning

Camp Drop Off

Every moment of parenting feels like a paradox. I am only 21 months into this thing but the tensions of parenting continue to surprise. There was a lot I expected about parenting but constantly questioning my instincts and feelings wasn’t one of them.

This week, we had another first in our family when our son attended camp. We have been fortunate to have been able to be at home with him with the help of family but both for work purposes and his own development, the time was right for him to start this new experience.

The newness of the first day made the drop off fairly manageable. There was some hesitation but mostly this place looked safe and had a lot of fun toys. It was on the second day where the tears really came. Wait, it seemed like he thought, I am doing this again and you’re leaving?? Sadness and clinging ensued before we finally parted ways.

Throughout that day, Lauren and I were both deep in thought. Would he be ok? Was he spending his whole day crying? When I received the pictures of him playing with a shopping cart, sitting on a teacher’s lap, and interacting with another child, I felt like in one fell swoop, my heart expanded and contracted. Those paradoxes, they keep coming.

Every step we’ve taken has been to the end of him developing independence, a sense of self, and courage for adventure. We’ve been moving toward this moment and here we were and there was way more sadness than anticipated. Life can be like that.

Outside of parenting, we all can recognize that feeling of working toward a particular end, getting there, and then feeling a certain sense of hesitation on what is to come. Will we be remembered even if we’re not there to see the manifestation of our hard work? Is it ok to feel that?

As we come to the end of the book of Bamidbar this week, the latter of the double portion we read Maaseh, begins with a detailed accounting of all the stops on the journey so far. Much of it is a reiteration of what we’ve seen before. When we reach the last stop of the journey, something jumps out at us1:

וַיַּחֲנ֤וּ עַל־הַיַּרְדֵּן֙ מִבֵּ֣ית הַיְשִׁמֹ֔ת עַ֖ד אָבֵ֣ל הַשִּׁטִּ֑ים בְּעַֽרְבֹ֖ת מוֹאָֽב׃ {ס}

they encamped by the Jordan from Beth-jeshimoth as far as Abel-shittim, in the steppes of Moab.

At first glance, it seems like all the other stops except for the fact that before this, we had only ever been to Shittim but never in a place called Abel-Shittim. Abel is one of those words that has multiple meanings. It has an ecological association meaning something like brook, forest, stream, or plain which is what you might find in a typical translation. But you might also notice its association with death as the root for the word aveilut-mourning. What could the Torah possibly be alluding to here with this nondescript geographic verse?

The Midrash Tanchuma, a collection of creative rabbinic teachings argues that this was the spot where Israel had their recent struggle with sexual impropriety. The Midrash’s take is that Israel made it all the way to the peak moment of connection with God and then almost blew it all with their poor decision making. This brought on the mourning and why this place of Shittim needed an addition to its name to mark the pain of this stop. They messed up and they mourned that error here.

An answer that is resonating more with me this year comes from the Abarbanel2. In addition to asking why there is a name change, he also wonders why the listing of the sites is appended to section on the divvying up of the land. Why not have stuck it back when we received the Torah at Mt. Sinai or later on when they’re actually in the land? Its placement here must be intentional in his eyes. Here’s his answer, commenting on Numbers 35:1

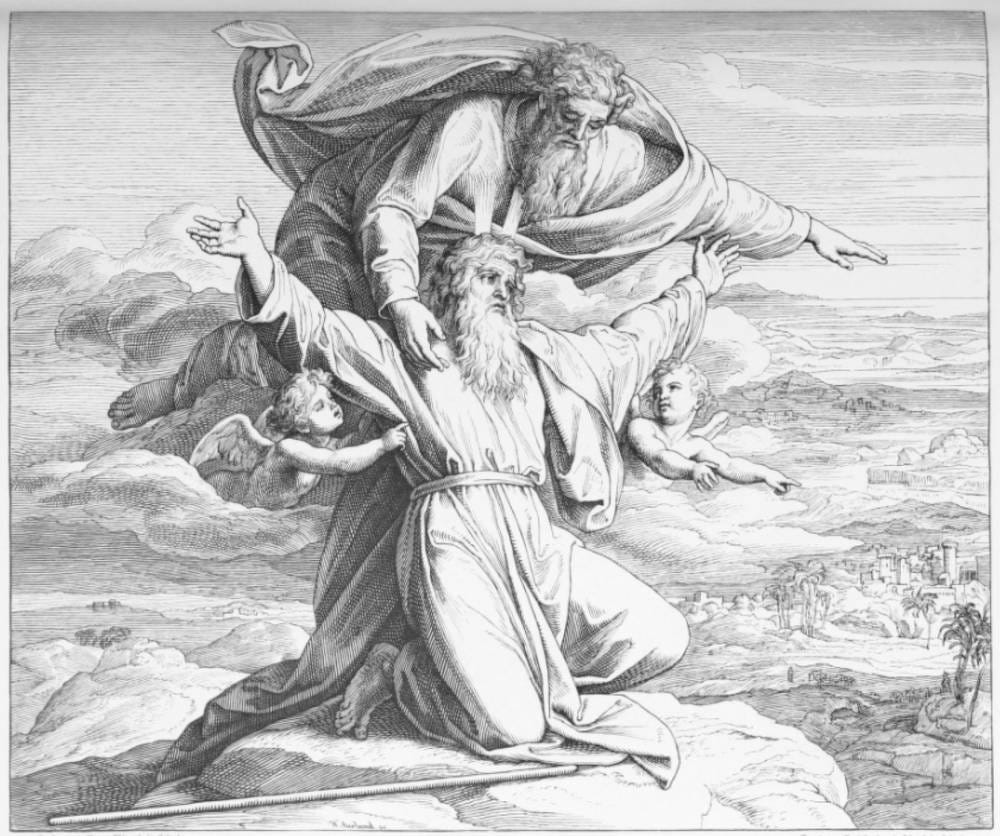

When Moses had finished writing down all of the journeys, from the day they left Egypt until they came to the Plains of Moab on the banks of the Jordan in Jericho, he remembered that God had said to him, “you will not cross the Jordan.” He saw that his days of reckoning and his end had come, and that this is where he would no doubt die.

So he made a sign for himself from the name of that place, and called it Avel-Sheetim, the ‘Mourning of the Acacias,’ for this is where they would mourn his death.

And because of this, he worried, and was very sad, and said, “I toiled, but rest I never found. I took this people out of Egypt, and I led them through the desert for forty years, to bring them into the Promised Land. And I then came to the bank of the Jordan, but I was not allowed to cross over and deliver it to my people.

Instead, another man will prepare it and deliver it to them. It was I who planted the fig tree, but I will not eat its fruit. Joshua, my attendant, will eat it, and the Land will be remembered for him. For he will conquer it and deliver it to Israel. And my name will never be mentioned again.”

And because of this, his heart twisted inside of him, and all of his bones trembled.

Instead of this being a place that marks communal error, it marks Moses’ dismay on not being around to see the fruits of his labor. He’s worked to this very moment and he’s been there every step of the way. But he won’t be there for the next part. His sadness is so palpable that it overtakes his whole body and roots him to the very ground upon which he is standing. Moses and the land are mourning.

To die is one thing. We all know that’s inevitable but to be forgotten is something more severe. What does it feel like to toil at something, working toward an end goal only to wonder if your efforts will be remembered? That is a deeply human experience.

This is when the Abarbanel responds to that feeling by answering his question of the textual placement. Namely:

Because Moshe was so overtaken by his sadness, God told him to command all these instructions regarding the eventual entry into the land. Even though you won’t be able to participate in them, your voice will be the one that commands it to happen. They will forever be linked to your name and legacy. In this moment, Moses is reassured as he now felt a sense that he too would be there in the land with them.

I get chills reading it. No, he won’t be there. But that’s not what he needs in this moment. Right here, in his pain, he needs the reminder that he’ll be with them in some form. They will always remember that he was the one who gave the charge. It may not fully remove his pain but it softens it enough because in that place, his connection is made permanent.

It feels so relatable. There I was this week, wondering “is Cal thinking of me? Is he sad because of me?” This teaching allayed some of my worries because it reminded me that we don’t always need to be there to be thought of. Our words, deeds, and other contributions can bring us to mind even when our physical presence does not. We have to trust the process.

That’s evident in parenting but also friendships, work, and so many areas of life. We work so hard to ensure different projects, products, and entities come to be but we’re not always privileged enough to see it. This piece of Torah reminds us that it’s ok. It’s ok to feel sadness about that and it’s ok to remind yourself that living within that plain of sadness is a sign that your voice and your legacy carries on.

Shabbat Shalom and Happy Weekend!

Numbers 33:49

Isaac ben Yehuda Abarbanel-15th century Portuguese biblical commentator

Nicely crafted, and super interesting.

Beautiful! We need only to remind ourselves of our parents, grandparents, and other loved ones who have passed, that we have not forgot their good deeds. And, hopefully, those we have touched, will remember ours, as well. Shabbat Shalom, hugs and love, and happy parenting! ❤️✡️

Zeta