Storytelling Monkeys

Antifragility

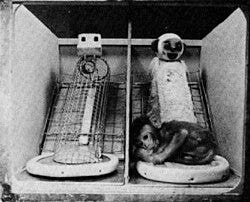

In the 1950’s and 60’s, psychologist Harry Harlow took infant monkeys from their biological mothers and gave them two inanimate surrogate mothers: one was a simple construction of wire and wood, and the second was covered in foam rubber and soft terry cloth. The infants were assigned to one of two conditions. In the first, the wire mother had a milk bottle and the cloth mother did not; in the second, the cloth mother had the food while the wire mother had none.

In both conditions, Harlow found that the infant monkeys spent significantly more time with the terry cloth mother than they did with the wire mother. When only the wire mother had food, the babies came to the wire mother to feed and immediately returned to cling to the cloth surrogate.

These stories are primarily known for producing groundbreaking empirical evidence for the primacy of the parent-child attachment relationship and the importance of maternal touch in infant development. Yet, I couldn’t help but think about them in relationship to the power of the stories we tell ourselves and our ability to mine comfort from them in deep moments of distress.

I was at a gathering this week where a question was posed to a small group of Jewish professionals:

Where is trust fraying in your lives right now?

Almost every person in the group answered in some form that their faith in institutions, both political and non-political is fraying or totally lost. This group was made up of senior rabbis, organizational executives, and academics. It was startling to hear that to a person, everyone is floundering within a total decay of societal trust, which brings me back to the monkeys.

What can we learn from Harlow’s research? Is there a way to use one of our greatest devices as a people, the story, to cultivate antifragility? Slightly different than resilience, antifragility argues that a given entity thrives under pressure. When practicing resilience, we persevere through a situation but remain the same after the fact. Antifragility helps us in our quest for improving and dynamism. We get through something and it shifts something within us.

Stories have the power to be antifragility mechanisms. They can push us to not just retell experiences but to use them to manifest something within us that makes us better equipped to live. We enter into one of the greatest parts of our Torah storytelling arcs this week, parshat Bo, which tells us of the latter part of the plagues and some of the first commandments around the retelling of the Exodus story.

In Exodus 10:2, after hardening Pharaoh’s heart once more, God declares that the divine signs are meant to:

וּלְמַ֡עַן תְּסַפֵּר֩ בְּאׇזְנֵ֨י בִנְךָ֜ וּבֶן־בִּנְךָ֗ אֵ֣ת אֲשֶׁ֤ר הִתְעַלַּ֙לְתִּי֙ בְּמִצְרַ֔יִם וְאֶת־אֹתֹתַ֖י אֲשֶׁר־שַׂ֣מְתִּי בָ֑ם וִֽידַעְתֶּ֖ם כִּי־אֲנִ֥י יְהֹוָֽה׃

and that you may recount in the hearing of your child and of your child’s child how I made a mockery of the Egyptians and how I displayed My signs among them—in order that you may know that I am יהוה.”

What is the purpose of telling a story in which God makes life harder for God’s people in order to make a mockery of their enemies? Wouldn’t it have been possible for God to have mocked our enemies without putting the impediment of pain and exile in front of us? This the question underlying the following penetrating comment from the Noam Elimelekh of Lizhensk1

When God, in God’s compassion, performs miracles on behalf of the people of Israel through an act of vengeance on their enemies, it awakens future oriented compassion and becomes activated for all generations of Israelites. So whenever ‘Israel’ finds itself faced with an enemy hell-bent on destroying it, God metes out punishment as a result of this original act. This is why the verse says, ‘in order that you tell your children…’ because when you tell the story, that very same compassion is awakened in the later generations.

In other words, telling the story of the Exodus is not simply a historic recounting. It is a divine opening of a portal between worlds. When we hear the story, we are reminded that in our people’s capacity for antifragility, we came through a painful situation better and transformed. After all, we began this story enslaved and degraded and came out of it free and dignified. Just as it was then, so it is for us now.

There are many ways to achieve this I imagine but one that is speaking to me now, especially as we face unprecedented crackdowns on civil liberties and the aforementioned fraying of trust is through storytelling. As much as we think what we’re facing is unique, and it may be in its context, the notion that things are falling apart around us isn’t new. That is where our prowess for telling a tale comes into play.

When the Dalai Lama had to flee Tibet for India, he needed to understand how to help his people survive a painful exile, so he turned to the Jewish community. After being told of the power of memory and storytelling, he was invited to a Pesach seder in 1997 and he shared the following:

In our dialogue with Rabbis and Jewish scholars, the Tibetan people have learned about the secrets of Jewish spiritual survival in exile: one secret is the Passover Seder. Through it for 2,000 years, even in very difficult times, Jewish people remember their liberation from slavery to freedom and this has brought you hope in times of difficulty. We are grateful to our Jewish brothers and sisters for adding to their celebration of freedom the thought of freedom for the Tibetan people.

On top of the magnificent image of the Dalai Lama consulting with the Jews, what he captured is the essence of our people’s strengths. For all of our struggles and troubles, this is one that has held us and nourished us all these centuries.

As we seek out interventions for what ails us, yearning for that comforting and nurturing place of warmth like Harlow’s monkeys, I think we need to refocus our energies on the power of stories. We need to tell them and retell them, plumbing our history for the powers of not just resilience but antifragility. Who are the exemplars from the past who have marshaled the Jewish communities in time of distress to find their resolve?

That is what we need now, among other things. In just a couple of months, we’ll begin the retelling of the passover story. In the meantime, can we seek out other stories that remind us of our strength? We are hardwired to seek out figures that provide nurture and comfort, not simply fulfilling our material needs. That can be found in our words and our stories in just as powerful ways.

Shabbat Shalom and Happy Weekend

1717–March 11, 1787, Poland, a member of the earliest strands of the Hasidic movement, 3rd generation.

The distinction between resilience and antifragility here is such a good framing. I think alot of ppl conflate the two but there's something uniquely generative about coming out transformed rather than just intact. The Harlow connection is clever too bc those monkeys weren't just surviving, they were seeking something that felt like meaning even when it wasnt practical. Been thinking about stories as coping mechanisms alot lately in my own life.

I like your premise about the importance of stories, but Bo? For me this story is painfully problematic. God hardens Pharoah’s heart? the plagues on the Egyptians? the “borrowing” of Egyptians jewels? The death of their first born? I’m unable to treasure a story such as this.