Fighting Battles

Learning from Abraham

Abraham Davis made a bad decision. In October of 2017, he borrowed his mom’s white minivan and drove to the home of a friend. They’d gotten drunk on cheap whiskey. Abraham agreed to drive his friend to a mosque in town. His friend drew swastikas and curses on the mosque’s windows and doors while Abraham stood watch in the driveway.

Abraham comes from a small town in Arkansas called Fort Smith that’s about exactly as you imagine a small town in Arkansas to be. As with many of our young people who find themselves in trouble with the law, Abraham came from a dysfunctional home, got lost within the local school system which brought on a self-propelled cycle of lack of drive and ambition that perhaps led him to make that fateful decision to drive the car to the Mosque.

In interviews after the legal process played out, Abraham shared the following thought:

Most of my life I’ve spent trying to train myself to become something that’s too strong to be broken through,”

Life had teed him up for a fight. Something was lodged in Abraham from the beginning, like a shard of glass in his heel. As he grew older, Abraham had trouble controlling his anger.

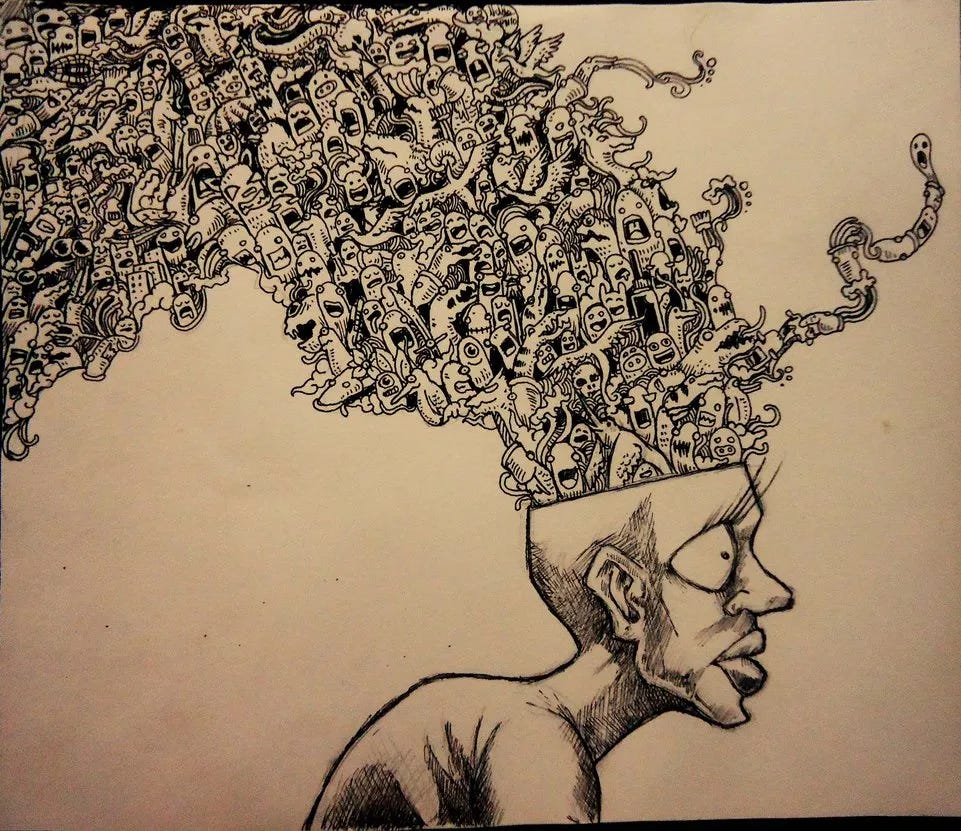

Like Abraham we all have aspects of ourselves that no matter how much we fight them, our predisposition toward a certain emotion or action can feel overwhelming and overpowering. Like Abraham, we get ourselves into trouble when we fall prey to those sides of ourselves. But the problem is not simply that we have those sides of ourselves; it’s what happened when we leave them unchecked. That lack of self-oversight led to Abraham defacing a mosque with hate-filled images and language.

As much as the beginning of the story reads pretty typically, the way the story ends is unexpected in the best possible way. Not only that but it also gives us a really important lesson as we enter into this period of the year and connects us to the portion this week.

In the beginning of our Parsha this week, we learn of various proscriptions related to what happens when you enter into war. Beginning at Deuteronomy 22:10, we read the following:

When you go to battle against your enemies, and God delivers them into your hands, and you capture captives, and see among the captives a woman, and you desire her, and you take her to be your wife; then you should bring her home to your house; and she shall cut her hair, and do her nails; and she shall put the remove her clothing of captivity, and shall remain in your house, and bemoan her father and her mother a full month; and after that you may have relations with her, and be her husband, and she shall be your wife. And it shall be, if you no longer desire her, then you shall send her away; but do not sell her at all for money, don’t deal with her as a slave, because you have afflicted her.

At first glance, we are shocked. First off, most of us haven’t faced war and further, the idea that a soldier, overcome by his carnal desires can just simply take a woman, seemingly subject her to a non-consensual makeover and then have her as a wife raises an immense amount of red flags. The Rabbis were also confounded by this text and they went about it in two different directions.

The first one is a bit more of a traditional interpretation. Rashi, the pre-eminent biblical commentator states as follows

Scripture is speaking only against the evil inclination . For if the Holy One would not permit her to him, he would take her illicitly.

He goes on to go through each step to describe how it will make the women repulsive to the man and not make him want to marry her. She grows her nails long as it is unbecoming. She changes clothes because, according to him, non-Jewish women in war time wore fancy clothes to seduce Jewish men. She sits around for a month so he stumbles around her sulking and comes to detest her for her grief-stricken cries. All in all, not the most pleasant read.

But not all that surprising. This is representative of the more mainstream way of viewing this story. Wanting to take the Torah at its surface level read, Rashi and others view this story as a cautionary tale for the Jewish (and I will add, male) audience. In this way, it allows the Torah to create a situation that will ultimately dissuade the young man from giving into his physical desires.

On the total other side of this is the Hasidic realm’s interpretation of this. Rav Moshe Chaim Ephrayim of Sudilkov better known as the Degel Machane Efraim saw less a recounting of possible events and more an allegorical narrative of the human psyche.

He says as follows

[This verse] we must explain homiletically: ‘When you go out to war against your enemies,’ this is right before one begins on his own volition to go to war against his evil inclination and with certainty, ‘God will give them into your hands.’

‘And when you see this beautiful woman,’ this is also a promise that even though God gives you an evil inclination, then you will see how God’s presence is actually this ‘beautiful woman,’ and that she is in a captivity of sorts. And ‘you desire her,’ in order to redeem her from captivity and take her for a wife.

His introduction signals something to us. He believes there’s no world in which the Torah meant for this section to be taken literally. It was all a framework for the inner workings of a person’s mind and soul.

He takes it at face value that we should be constantly prepping to enter into a battle with “our enemies,” which are our evil inclinations. We should be vigilant in fighting back against the desires inside of us that strive to turn us down the wrong path. As ominous as that sounds, we should remember he says that the verses promises with certainty that God will deliver them into your hands. Yes, the war is inevitable but so is victory. That may be more aspirational than literal as we all know fighting our demons ends in plenty of losses and slip ups. Nonetheless, our tradition nudges us to believe.

His next step is I think then his most beautiful and poetic. He preempts the argument that would wonder why in the world God gave us this evil inclination in the first place by saying that hidden in the evil inclination is God’s shekhinah(earthly presence). If we dig a little deeper beyond the desire, we’ll recognize something holy inside of it. And the holy kernel that’s there is the opportunity that an evil desire presents, which is a chance to free it and return it to its ideal state...or, in other words, teshuvah, one of our major themes this time of year. Teshuvah is the work we do to return our lives to how they ought to be.

His take reframes a section of the Torah that is troubling and turns it on its head. This is not about a war on the battlefield. This is the everyday battles that each of us face, when we are dueling with those parts of ourselves that sometimes get the better of us. We can all find faith in the fact that our tradition tells us that even in those inclinations, there is a chance for Godly redemption.

This brings us back to Abraham Davis from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Abraham had spent his entire life trying to become strong enough to protect his family, but it was not until jail, he said, that he realized that he was the one who had inflicted the most hurt. He felt a powerful urge to set things right.

I was just so tired of doing the wrong thing.

He then penned a letter to the mosque:

Dear Masjid Al Salam Mosque, I know you guys probably don’t want to hear from me at all but I really want to get this to y’all. I’m so sorry about having a hand in vandalizng your mosque. It was wrong and y’all did not deserve to have that done to you. I hurt y’all and I am haunted by it. And even after all this you still forgave me. You are much better people than I. I don’t know what’s going to happen to me, and that is honestly really scary. But I just wouldn’t want to keep going on without trying to make amends. I wish I could undo the pain I helped to cause. I used to walk by your mosque a lot and ask myself why I would do that. I don’t even hate Muslims. Or anyone for that matter. All in all, I just want to say I’m sorry.

It was in his lowest moment that Abraham finally met with his darkest urges. He wrestled with them and was felled by them. But in the end, he found some amount of redemption because he was able to transform them into something Godly...the ability to recognize a fault and say sorry. It sounds contrived but it’s such incredibly hard work.

Most of us are fortunate in that our dealings with our own demons don’t end in our incarceration, but I imagine we can all find connected lines: our anger, our materialism, or our ego. You can fill in your own blank but when you do, try to remember the lesson of Abraham.

In the end, he served his time, paid his restitution and was forgiven by the Mosque’s community members. It’s a cycle we should all strive for because as the Degel Machane Ephraim tells us, ki tetze lamilchama, when you go to battle isn’t a rarity; it’s a certainty.

For the last few weeks and continuing through High Holidays Jews around the world have been saying Psalm 27. Within it, the Psalmist uses the imagery of hope in God and strengthening our hearts to respond to being surrounded by enemies. It’s an image that dovetails here. We will face these battles. In addition to having faith, we must also learn to give our heart courage and strength. As Abraham told us, that’s all about the ability to confront your demons, see the divinity in them, and redeem them through a confrontation with truth and accountability.

Shabbat Shalom and Happy Weekend

Thought provoking, as always! I struggle alot with the why! If one believes we are made in God’s image, then God also must struggle with the inclination of good and evil, perhaps falling short, and also asking for forgiveness? I strive to think good thoughts, and do good deeds, but, mainly because, it just feels good! Shabbat Shalom, and hugs and love.❤️✡️